A striking new study has tracked the effects of extreme isolation on the brains of nine crew members who spent 14 months living on a remote research station in Antartica. The study presents some of the first evidence ever gathered to show how intense physical and social isolation can cause tangible structural changes in a person’s brain, revealing significant reductions in several different brain regions. Despite the small size of the study the conclusions echo years of research correlating solitary confinement and sensory deprivation with mental health issues, and suggest social isolation may fundamentally change the structure of a person’s brain.

The lonely brain

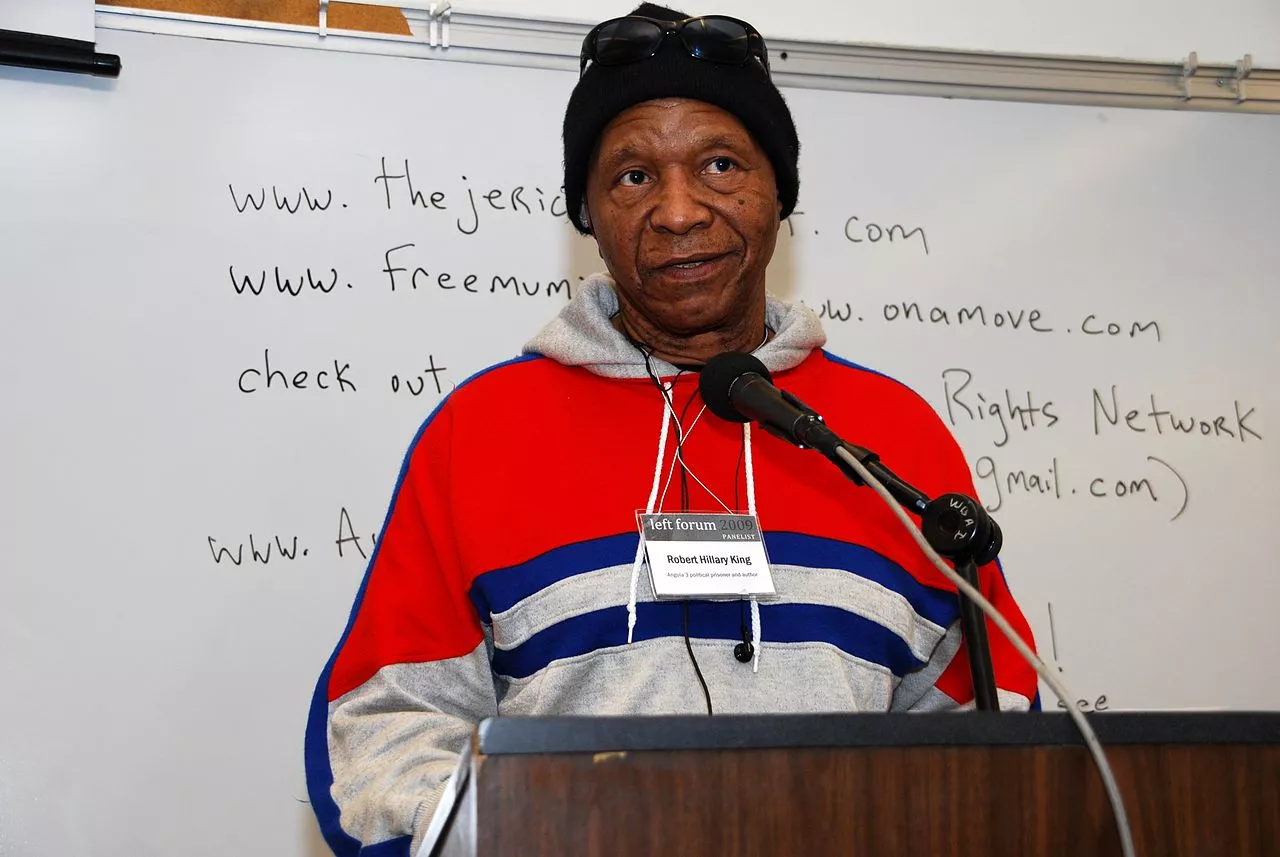

In 1969 Robert King was arrested and convicted for a robbery he maintained he did not commit. Three years later an inmate on King’s block was murdered. King was blamed for the murder, and despite his claims of innocence he was convicted of murder and sent to solitary confinement.

For the next 29 years King lived his life alone in a tiny cell, only allowed short bursts of time outside, and even then he was not allowed to talk or socialize with other prisoners. In 2001 his conviction for murder was overturned and he was released. But the damage, both psychological and physiological, caused by the years of solitary confinement persisted.

“When I walked out of Angola, I didn't realise how permanently the experience of solitary would mark me,” King recounted back in 2010. “Even now my sight is impaired. I find it very difficult to judge long distances – a result of living in such a small space.”

King appeared on a discussion panel in late 2018 at the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience. Facing a room full of neuroscientists, and alongside several researchers, King offered a lucid first-hand account of how extended solitary confinement effected his cognitive functions. King’s memory has been permanently impaired by the experience, and for a time after he was released in 2001 he was unable to properly recognize human faces.

“People want to know whether or not I have psychological problems, whether or not I’m crazy—‘How did you not go insane?’” King was reported saying at the 2018 meeting. “I look at them and I tell them, ‘I did not tell you I was not insane.’ I don’t mean I was psychotic or anything like that, but being placed in a 6 x 9 x 12–foot cell for 23 hours a day, no matter how you appear on the outside, you are not sane.”

Scientists have known for a long time that social isolation can lead to a variety of negative health outcomes. Loneliness is not just damaging to a person’s mental health, but it’s increasingly being linked to many physiological symptoms such as inflammation and cardiovascular disease. Some research has even suggested loneliness can increase a person’s risk of early death as much as obesity or smoking.

We know humans are social animals, and while there are decades of research examining the negative psychological effects of chronic isolation, remarkably little has been conducted on the physiological effects of isolation.

Animal studies have clearly demonstrated long stretches of isolation can alter the structure of the brain. In particular, research has shown when animals are isolated from social contact changes to their hippocampus can be detected.

It has been challenging, however, for scientists to study these acute changes in humans. After all, there is no ethics panel on Earth that would approve some kind of extreme isolation brain study. The most obvious way to examine the effect of isolation on a human brain would be to image prisoners before and after long stretches in solitary confinement, but in news that would surprise no one, prisons have been reticent to allow scientists in for those kinds of studies. What would the implications be for mass incarceration if solitary confinement was shown to be physiologically damaging to a human brain?

14 months in Antarctica

One way to potentially study the effects of long-term isolation on the human brain is to look at those bold individuals who spend extended periods of time at remote Antarctic research stations. In a new correspondence published in the New England Journal of Medicine, a team of scientists has described the results of a novel brain imaging study that tracked nine subjects who spent 14 months at the isolated German Neumeyer III station.

Alongside MRI brain data gathered before and after the expedition, the subjects were monitored during their time on the station for levels of a key protein called brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and cognitively tested for signs of decline.

The experience of these nine individuals is obviously not entirely analogous to that of complete social isolation, or a similar length of time faced by a prisoner in solitary confinement, but the researchers do note the characteristics of the expedition offer extreme environmental monotony and extended stretches of relative isolation. For several winter months the research station is shrouded in continual darkness, and entirely cut off from the outside world. There is a window of only three months every year when the station is accessible for food deliveries or personnel evacuations.

The results of this small study were striking. The brain scans completed at the end of the 14 month expedition revealed an area of the hippocampus called the dentate gyrus had shrunk in all subjects. Several other hippocampal regions also displayed volume reductions, while mean grey matter decreases were detected in the left parahippocampal gyrus, the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and the left orbitofrontal cortex.

The study revealed a distinct correlation between these structural brain changes and reductions in BDNF serum concentrations. BDNF is a protein known to be essential for healthy brain function. It encourages the formation of new synapses and neurons in the brain. Within three months of arrival at the remote Antarctic station, the study participants displayed a drop in BDNF levels to below baseline starting levels.

Even more importantly, these BDNF levels had not returned to normal at the end of the study period, one and a half months after returning from the Antarctic site. The researchers hypothesize the drop in BDNF levels may be what causes the subsequent structural brain changes.

Alexander Stahn, lead researcher on the new study, suggests his team’s results should be read with caution. The small cohort, and other potential unstudied causal mechanisms, limit how strong one can link the social and environmental deprivations to the brain changes. However, he does note a solid body of animal study supports the veracity of his team's hypothesis.

"Given the small number of participants, the results of our study should be viewed with caution," explains Stahn. "They do, however, provide important information, namely - and this is supported by initial findings in mice - that extreme environmental conditions can have an adverse effect on the brain and, in particular, the production of new nerve cells in the hippocampal dentate gyrus."

We know how important social contact is, and we know isolating human beings from one another can be damaging. From faster rates of cognitive decline seen in senior citizens with little social contact, to over 50 percent of cases of self-harm in jail attributed to solitary confinement, it is becoming increasingly clear how damaging social isolation can be to a human being.

Yet we still know extraordinarily little about the physical effects of isolation on our body and brain. And these are questions we will need to answer if we have ambitious plans to do things such as send astronauts on long extended trips to Mars. Or perhaps we need the answers for more ethical earthbound questions, such as exactly how humane is solitary confinement if it generates structural damage to a human brain?